Speaker

Description

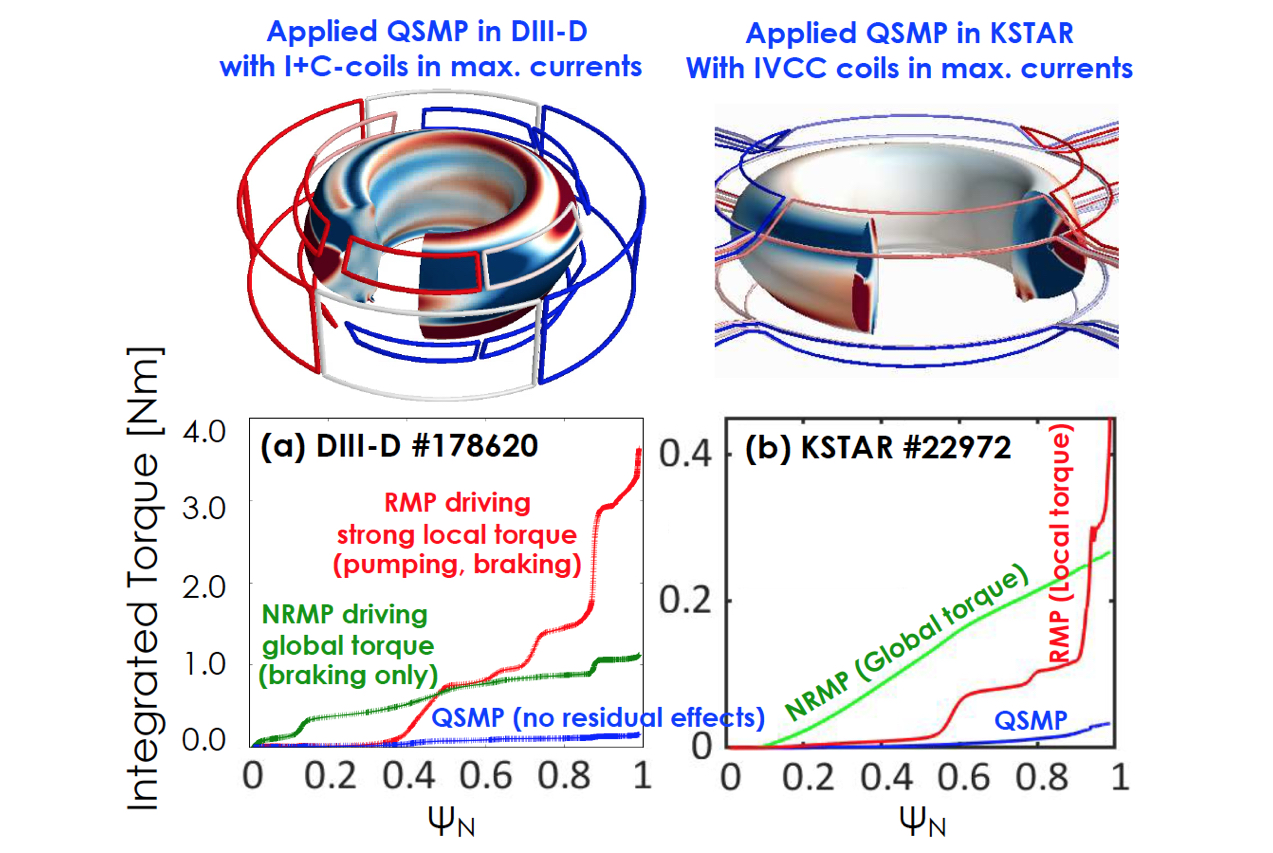

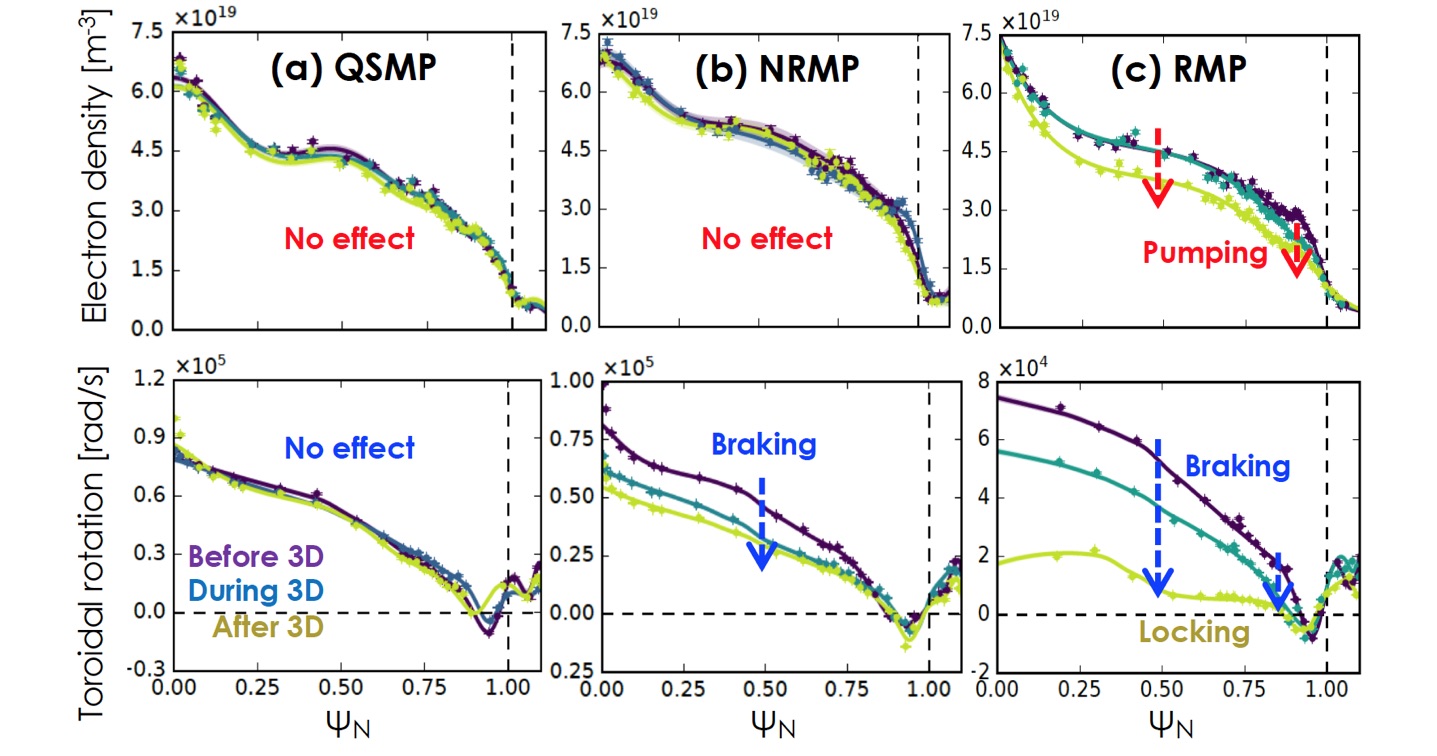

A predictive 3D optimizing scheme in tokamaks is revealing a robust path of error field correction (EFC) across both resonant and non-resonant field spectrum. The new scheme essentially finds a way to deform tokamak plasmas in the presence of non-axisymmetric error fields while restoring a quasi-symmetry in particle orbits as much as possible. Such a “quasi-symmetric magnetic perturbation” (QSMP) has been predictively optimized by general perturbed equilibrium code (GPEC) {1} and successfully tested in DIII-D and KSTAR tokamak plasmas (Fig. 1). The QSMPs in experiments demonstrated no performance degradation despite the large overall amplitudes of 3D fields, as clearly compared with a resonant magnetic perturbation (RMP) or a typical non-resonant magnetic perturbation (NRMP) (Fig. 2). The results indicate that the tokamak EFC can be improved beyond the present resonant-overlap EFC approach alone, if the residual non-axisymmetry can be further compensated to a level of QSMP. The studies also validate that the torque response matrix, a unique product of the GPEC formulation, can be used to assess the degree of not only resonant but also non-resonant EF correction – which has been desired by ITER for a long time.

Successful EFC is critical in tokamaks for preventing disruptions, especially in next-step devices like ITER due to unfavorable scaling with high $B_T$ and $\beta_N$. Improved understanding of plasma response in the last decade allowed the development of a more reliable approach than earlier ones, using the resonant-overlap field {2}, i.e. error field component that triggers the dominant RMP response. This led to the successful multi-machine scaling of resonant EF thresholds against disruptive locked modes across wide operational regimes and 3D field spectra, including the n=1 and n=2 toroidal mode numbers {3}. Recent highlights include the successful EFC against 2/1 locked modes due to the EF by the high-field-side (HFS) using the low-field-side (LFS) coils in COMPASS and NSTX-U, despite an overall increase of non-axisymmetry in both cases. These experiments, however, also posed an important question that must be addressed; how to quantify and compensate the next key mode, or simply NRMPs. The residual EFs after the dominant RMP correction remained disruptive during L-H transitions in COMPASS {4}, and significantly degraded performance in evolving discharges in NSTX-U {5}. Such residual EFs also generally drive rotational damping through uncorrected NRMPs as shown in DIII-D {6}.

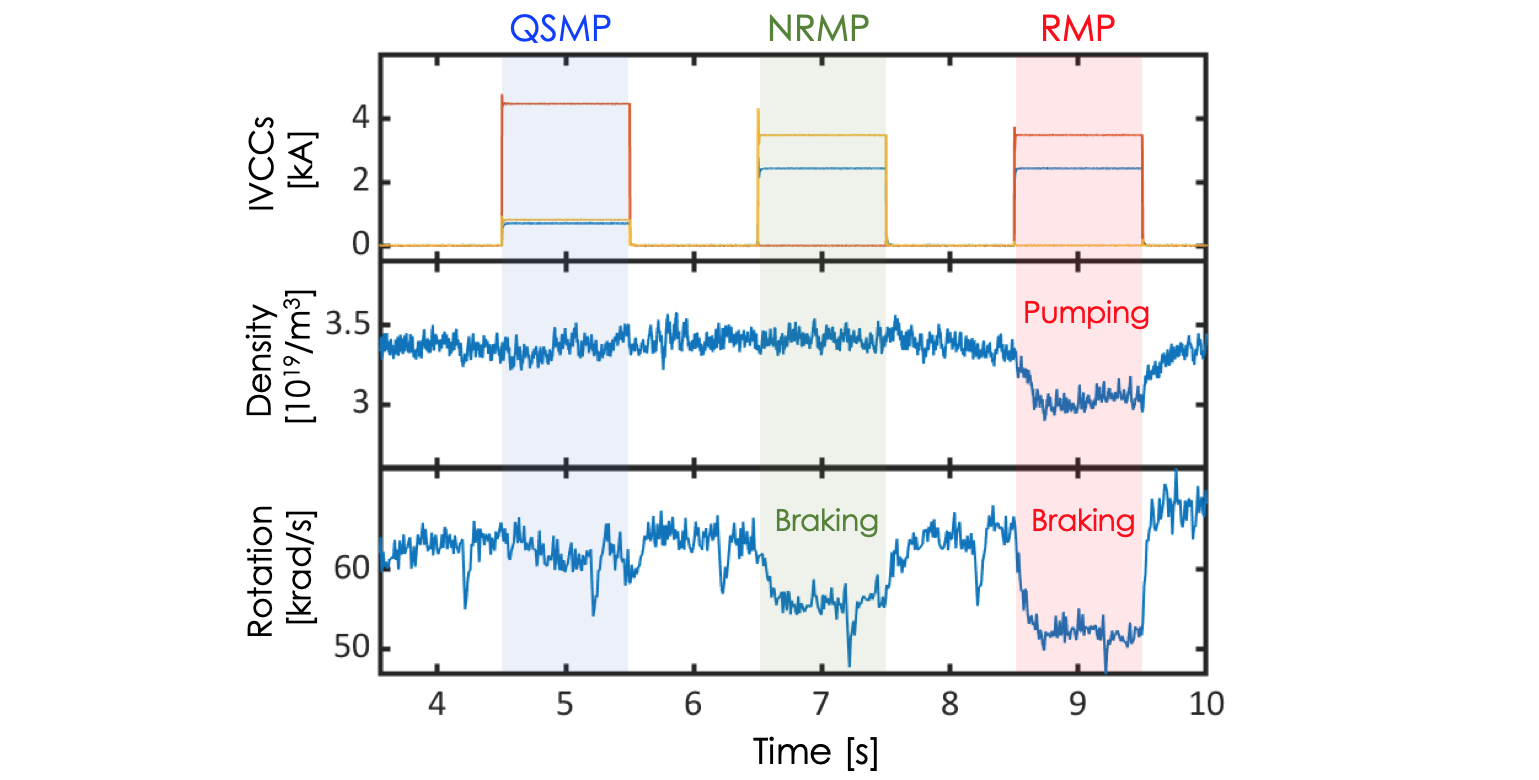

It turns out that the residual EF effects can be almost entirely suppressed if the additional coils are available to minimize the neoclassical toroidal viscosity (NTV) simultaneously with the dominant RMP correction. To experimentally demonstrate this, it is necessary to have 3 rows of coils – one coil to generate a strong proxy EF and RMP response, another coil to compensate the dominant resonant response while leaving a NRMP response, and yet another to minimize the remaining NRMP-driven NTV and leave only QSMPs. Figure 1 shows the n=1 coil configurations designed to test QSMPs in DIII-D and KSTAR, with the predicted torque profiles compared to RMPs and NRMPs. One can see that the local torque near resonant layers in RMP is significantly reduced in NRMP, and the global non-resonant torque in NRMP is minimized in QSMP. These fields were applied with maximum coil currents to high performance ($\beta_N\sim3$) DIII-D plasmas with ~9MW NBI power. As shown in Fig. 2, there was no change observed in performance and confinement during the QSMP, compared to the clear rotation braking with the NRMP or the strong density pumping and rotation braking with the RMP which eventually led to a locked mode. Surprisingly, the NRMP remained disruptive during L-H transition when tested with marginal DIII-D H-modes, but the effect could be eliminated in QSMP, suggesting a potential resolution to the aforementioned issue in COMPASS with the dominant RMP correction alone. The QSMP optimization was also performed in KSTAR discharges ($\beta_N\sim2$), again showing no performance changes in contrast to the RMP and NRMP (Fig. 3). Note that KSTAR can make a pure NRMP with strong NTV {7} as can be seen by complete elimination of local resonant torque in Fig. 1, by taking advantage of it’s 3 rows of in-vessel coils and also low intrinsic EF.

EFC will never eliminate all small 3D fields in a tokamak and it, in fact, commonly increases them when the correction coils are shaped very differently from the intrinsic error field sources. Instead, one can identify a safe and robust 3D state such as a QSMP and see if it is accessible in the course of EFC. The self-consistent perturbed equilibrium calculations with neoclassical transport in GPEC offer a torque response matrix $T(\psi)$, from which one can immediately predict the torque profile by quadratic operation $\Phi^\dagger\cdot T\cdot\Phi$, where $\Phi$ is a field spectrum vector on a toroidal surface or coil vector representing its amplitude and phase by complex numbers {1}. The minimum eigenstate of $T(\psi)$ then represents the best possible way to deform the plasma while sustaining the minimum variation in the field strength or action variation ($\delta B_L \approx 0$, $\delta J \approx 0$) as well as minimum resonant parallel current and corresponding resonant torque, i.e. achieving quasi-symmetry.

In summary, new experiments demonstrated that a QSMP could be an ideal EFC state without any performance degradation, offering a new and complementary EFC approach in addition to the present resonant-overlap method and also a possible resolution on non-resonant error field correction problem. The torque response matrix in GPEC will enable the QSMP optimization in more complicated 3D tokamak environments such as ITER with many more 3D coils and potential EF sources. This QSMP is also an interesting concept in and of itself, as it holds a sizable local perturbation at least near the divertor and its possible utility will be further discussed. *This research was supported by U.S. DOE contracts #DE-AC02-09CH11466 (PPPL), #DE-FC02-04ER54698 (DIII-D), and also by the Korean Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (KSTAR).

{1} J.-K. Park and N. C. Logan, Phys. Plasmas 24, 032505 (2017)

{2} J.-K. Park, N. C. Logan et al., “Assessment of EFC criteria for ITER”, ITPA MDC-19 Report (2017)

{3} N. C. Logan, J.-K. Park et al., “Scaling of the n=2 error field threshold in tokamaks”, submitted to Nucl. Fusion (2020)

{4} T. Markovic et al., the 45th EPS DPP in Prague, Czech Rep. (2018)

{5} N. Ferraro, J.-K. Park et al., Nucl. Fusion 59, 086021 (2019)

{6} C. Paz-Soldan, N. C. Logan et al., Nucl. Fusion 55, 083012 (2015)

{7} Y. In, Y. M. Jeon et al, Nucl. Fusion 59, 056009 (2019)

| Affiliation | Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory |

|---|---|

| Country or International Organization | United States |